Cells, life’s fundamental units, exhibit diverse structures mirroring their specialized functions; understanding these relationships, as detailed in research, is crucial for biological study.

Cell Theory: The Foundation

Cell theory, a cornerstone of biology, posits that all living organisms are composed of cells – the basic structural and functional units of life. Developed through the work of Schleiden, Schwann, and Virchow, it establishes that all cells arise from pre-existing cells.

This foundational principle underscores the universality of cellular organization, from single-celled organisms to complex multicellular beings. Understanding this theory is paramount when studying cell anatomy and embryology, as it provides the framework for comprehending life’s processes.

Historical Perspective on Cell Discovery

Early observations, aided by the invention of the microscope, initiated the journey of cell discovery. Robert Hooke first described “cells” in cork, while Leeuwenhoek detailed living cells, like those in blood.

Subsequent research by Schleiden and Schwann extended these findings, proposing that both plants and animals are composed of cells. Virchow later clarified that cells originate from pre-existing cells, solidifying the cell theory. This historical progression reveals a gradual unveiling of life’s fundamental building blocks.

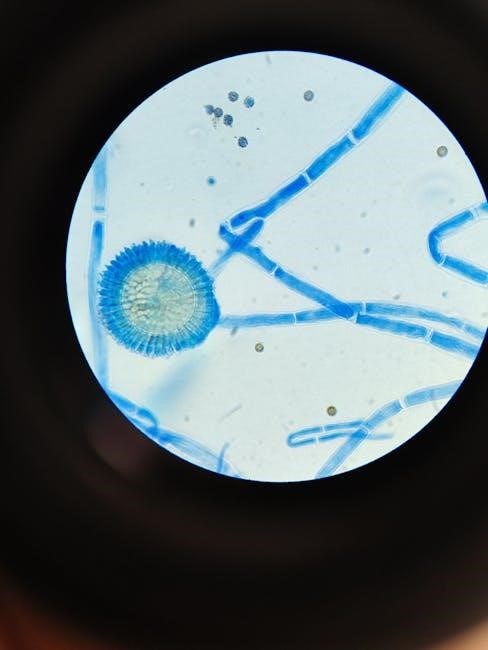

Cellular Components: A Detailed Look

Cells comprise a plasma membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus, each with distinct structures. These components work in harmony to facilitate life’s processes and functions.

The Cell Membrane: Structure and Transport

The cell membrane, a vital boundary, consists of a phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins. This structure regulates what enters and exits the cell, maintaining internal homeostasis. Transport mechanisms include passive diffusion, facilitated diffusion, and active transport, each crucial for cellular function.

These processes ensure nutrient uptake and waste removal. Junctions, like tight and gap junctions, further modulate membrane permeability and intercellular communication, impacting overall cellular activity and tissue organization. Understanding these features is key to comprehending cellular life.

The Nucleus: Control Center of the Cell

The nucleus, the cell’s command center, houses the genetic material – DNA – organized into chromosomes. This structure dictates cellular activities through gene expression. The nuclear envelope, with its pores, regulates transport between the nucleus and cytoplasm, controlling access to genetic information.

It’s essential for replication and transcription. Understanding the nucleus’s structure and function is paramount to comprehending cell growth, division, and differentiation, ultimately defining the cell’s identity and role within the organism.

Cytoplasm and its Organelles

Cytoplasm, the gel-like substance within a cell, encompasses all organelles. These structures – like the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus – perform specific functions essential for cell survival. The cytoplasm provides a medium for biochemical reactions and supports organelle suspension.

Organelles collaborate to synthesize proteins, process molecules, and generate energy. Their intricate structure directly relates to their function, highlighting the cell’s remarkable efficiency. Studying these components reveals the complexity of cellular processes and their coordinated activity.

Endoplasmic Reticulum: Rough and Smooth

The endoplasmic reticulum, a network of membranes, facilitates lipid and protein synthesis, alongside material transport; its structure increases surface area for reactions.

Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum: Protein Synthesis

Rough ER’s surface, studded with ribosomes, is the primary site of protein synthesis for secretion or membrane integration. Ribosomes translate mRNA into proteins, which then enter the ER lumen for folding and modification. This process ensures proper protein conformation and functionality.

The ER membrane provides a protected environment for these crucial steps, preventing interference from the cytoplasm. Modified proteins are then packaged into transport vesicles, budding off from the ER to deliver their cargo to the Golgi apparatus for further processing and distribution throughout the cell.

Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum: Lipid Synthesis and Detoxification

Smooth ER lacks ribosomes, specializing in lipid synthesis – crucial for cell membrane growth and organelle membranes. It manufactures phospholipids and steroids, vital for cellular structure and signaling. Furthermore, smooth ER plays a key role in detoxification, metabolizing drugs and poisons, particularly in liver cells.

Enzymes within the smooth ER modify harmful substances, making them more water-soluble for excretion. It also stores calcium ions, essential for muscle contraction and other cellular processes, acting as a versatile metabolic hub within the cell.

ER as a Transportation Network

The endoplasmic reticulum functions as a cellular highway, providing routes for molecule transport. Its interconnected membrane system facilitates movement of proteins and lipids synthesized within the ER to other cellular destinations, like the Golgi apparatus.

These transportation routes ensure efficient delivery of essential components throughout the cell. The ER’s extensive network increases surface area for chemical reactions, optimizing metabolic processes. This internal transport system is vital for maintaining cellular organization and function, enabling coordinated activity.

Golgi Apparatus: Processing and Packaging

The Golgi modifies, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids for transport, ensuring proper cellular function through efficient delivery of these vital molecules.

Golgi Structure and Function

The Golgi apparatus, a central organelle, comprises flattened, membrane-bound sacs called cisternae, arranged in stacks. These stacks exhibit distinct polarity – a cis face receiving vesicles and a trans face dispatching them. Its primary function involves processing and packaging macromolecules, particularly proteins and lipids, synthesized elsewhere in the cell.

This organelle modifies these molecules, adding sugars or phosphate groups, and then sorts and packages them into vesicles for delivery to other organelles or secretion outside the cell. The Golgi’s structure directly supports its function, providing a dedicated space for these crucial modifications and trafficking events.

Protein Modification and Sorting

Proteins, arriving from the endoplasmic reticulum, undergo significant modifications within the Golgi apparatus. Glycosylation, the addition of sugar molecules, is a key process, influencing protein folding, stability, and targeting. Phosphorylation, adding phosphate groups, regulates protein activity.

Following modification, proteins are sorted based on destination. Specific signals guide them into different vesicles destined for lysosomes, the plasma membrane, or secretion; This precise sorting ensures proteins reach their correct locations, enabling proper cellular function and maintaining cellular organization.

Mitochondria: Powerhouse of the Cell

Mitochondria, with their unique structure, drive ATP production via cellular respiration, providing the energy necessary for all cellular activities and life itself.

Mitochondrial Structure

Mitochondria possess a distinctive double-membrane structure. The outer membrane is smooth, while the inner membrane is folded into cristae, significantly increasing surface area.

These cristae are crucial for housing the proteins involved in ATP synthesis. The space between the membranes is the intermembrane space, and the space enclosed by the inner membrane is the mitochondrial matrix.

Within the matrix, you’ll find mitochondrial DNA, ribosomes, and enzymes essential for cellular respiration. This compartmentalization optimizes the efficiency of energy production, a key aspect of cellular function.

ATP Production and Cellular Respiration

Mitochondria are renowned as the “powerhouses” of the cell, primarily due to their role in ATP (adenosine triphosphate) production. This occurs through cellular respiration, a complex process involving glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and the electron transport chain.

The electron transport chain, located on the inner mitochondrial membrane, utilizes the proton gradient to generate a substantial amount of ATP.

This energy currency fuels various cellular activities, highlighting the vital link between mitochondrial structure and efficient energy conversion for life’s processes.

Lysosomes and Peroxisomes: Cellular Recycling

Lysosomes degrade cellular waste via enzymes, while peroxisomes metabolize toxins; both organelles are essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis and recycling components.

Lysosomal Function: Degradation and Autophagy

Lysosomes are membrane-bound organelles acting as the cell’s digestive system. They contain hydrolytic enzymes capable of breaking down various biomolecules – proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids – derived from both internal and external sources. This degradation process is vital for removing damaged organelles and cellular debris.

Autophagy, a crucial lysosomal function, involves the self-eating of cells, where cytoplasmic components are enclosed within vesicles and delivered to lysosomes for degradation. This process is essential for cellular quality control, responding to stress, and maintaining cellular health. Dysfunctional autophagy is linked to numerous diseases.

Peroxisome Roles in Metabolism

Peroxisomes are small, single-membrane organelles involved in diverse metabolic pathways. A key function is the breakdown of very long-chain fatty acids through beta-oxidation, generating acetyl-CoA which then enters other metabolic routes. They also detoxify harmful compounds, like alcohol, by oxidizing them.

Crucially, peroxisomes produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a byproduct, which is then converted to water by the enzyme catalase, preventing oxidative damage. These organelles play a significant role in lipid metabolism and contribute to cellular homeostasis.

Cytoskeleton: Structural Support and Movement

Microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments form the cytoskeleton, providing structural support, enabling cell movement, and facilitating intracellular transport.

Microtubules, Microfilaments, and Intermediate Filaments

Microtubules, hollow tubes composed of tubulin, are crucial for cell shape, chromosome segregation during division, and organelle movement via motor proteins. Microfilaments, built from actin, drive cellular motility, muscle contraction, and cytoplasmic streaming, influencing cell shape changes.

Intermediate filaments, diverse in composition, provide tensile strength and anchor organelles, maintaining cell integrity. These three components dynamically interact, forming the cytoskeleton – a network essential for structural support, intracellular transport, and overall cellular function, as highlighted in cell biology research.

Cell Shape, Motility, and Intracellular Transport

Cell shape, dictated by the cytoskeleton, isn’t static; it dynamically adjusts for functions like adhesion and movement. Motility, powered by actin and microtubules, enables cell migration – vital in development and immune responses.

Intracellular transport relies on motor proteins ‘walking’ along microtubule tracks, delivering organelles and vesicles. This efficient system ensures proper cellular organization and function, as detailed in studies of cell structure and its impact on biological processes, maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Cellular Junctions: Communication and Adhesion

Cellular junctions – tight and gap junctions – facilitate crucial cell-to-cell communication and adhesion, forming barriers and enabling direct cytoplasmic connections.

Tight Junctions: Creating Barriers

Tight junctions are crucial for forming impermeable barriers between epithelial cells, preventing leakage of molecules across cellular layers. These junctions achieve this through a network of proteins – claudins and occludins – that tightly seal adjacent cells together.

This close association restricts paracellular transport, controlling the passage of substances and maintaining cellular polarity. They are vital in organs like the intestines and bladder, ensuring selective permeability and protecting underlying tissues. Their structural integrity is essential for maintaining homeostasis and preventing harmful substances from crossing the epithelial barrier.

Gap Junctions: Direct Communication

Gap junctions facilitate direct electrical and metabolic communication between neighboring cells. These junctions are formed by connexin proteins, which assemble into channels called connexons, aligning between adjacent cells. This creates a direct cytoplasmic connection, allowing ions, small molecules, and electrical signals to pass freely.

This intercellular communication is vital for coordinated functions in tissues like the heart and nervous system, enabling rapid responses and synchronized activity. Gap junctions contribute to tissue homeostasis and are crucial for processes like embryonic development and wound healing.

Red Blood Cell Structure and Function

Red blood cells, with their unique morphology, efficiently transport oxygen throughout the body; their structure directly supports this vital physiological function.

Morphology of Human Red Blood Cells

Human red blood cells (erythrocytes) possess a distinctive biconcave disc shape, lacking a nucleus and most organelles. This unique morphology maximizes surface area for efficient gas exchange, facilitating rapid oxygen diffusion. Their flexible structure allows them to navigate narrow capillaries, ensuring oxygen delivery to tissues. The absence of a nucleus creates more space for hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein. This specialized shape and internal composition are crucial adaptations for their primary function: transporting oxygen from the lungs to the body’s tissues and carbon dioxide back to the lungs.

Adaptations for Oxygen Transport

Red blood cells exhibit remarkable adaptations for efficient oxygen transport. Primarily, their high hemoglobin concentration maximizes oxygen-carrying capacity. The biconcave shape increases surface area, enhancing gas exchange rates. Furthermore, the lack of organelles maximizes space for hemoglobin. Their flexibility allows passage through narrow capillaries, delivering oxygen to tissues effectively. The protein spectrin maintains cell shape and deformability. These structural features, coupled with hemoglobin’s oxygen-binding properties, ensure optimal oxygen delivery throughout the body, supporting cellular respiration and overall organismal function.

Structure-Function Relationship of Biomolecules

Biomolecules – lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins – demonstrate a critical structure-function link; their unique shapes dictate biological activity, as highlighted in research.

Lipids, Nucleic Acids, and Proteins

Lipids form cellular membranes and store energy, their structure influencing membrane fluidity and permeability. Nucleic acids, DNA and RNA, encode genetic information; their double helix or single-strand structure enables replication and protein synthesis.

Proteins, with complex 3D structures, catalyze reactions, provide structural support, and transport molecules. These biomolecules’ functions are intrinsically tied to their specific arrangements, impacting all cellular processes. Understanding these relationships is foundational to comprehending biological activity and cellular mechanisms, as detailed in comprehensive cell studies.

Impact of Structure on Biological Activity

Biological activity is profoundly dictated by molecular structure; a protein’s shape determines its enzymatic specificity, while lipid composition affects membrane permeability. Nucleic acid sequences dictate genetic code translation. Even minor structural alterations can drastically change function.

This structure-function relationship is a cornerstone of biology, influencing everything from cellular signaling to metabolic pathways. Research emphasizes that understanding these intricate connections is vital for deciphering cellular processes and developing targeted therapies, as highlighted in detailed cell structure analyses.

Half-Cell and Full-Cell Systems in Battery Research

Half-cell and full-cell systems differ in structure and research focus; half-cells examine individual electrode reactions, while full-cells assess complete battery performance.

Definitions and Core Structures

Half-cells, in battery research, isolate a single electrochemical reaction – either oxidation or reduction – providing focused analysis of electrode materials and their behavior. Their core structure typically includes a working electrode, a reference electrode, an electrolyte, and a counter electrode. Conversely, full-cells represent complete battery configurations, mirroring real-world applications with both anode and cathode materials integrated.

These systems assess overall battery performance, including capacity, voltage, and cycle life. The distinction lies in the scope of investigation: half-cells dissect fundamental processes, while full-cells evaluate integrated system functionality, crucial for practical device development and optimization.

Differences in Research Focus and Applications

Half-cell research primarily focuses on understanding the electrochemical properties of individual materials, like anode or cathode components, optimizing their performance through structural modifications and compositional adjustments. This detailed analysis aids in identifying limiting factors and improving material stability. Full-cell studies, however, prioritize evaluating the combined performance of all battery components, assessing factors like interfacial resistance and overall energy density.

Applications differ significantly; half-cells are vital for fundamental materials science, while full-cell testing is essential for validating battery designs and predicting real-world performance characteristics.